FOREWORD TO THE ENGLISH EDITION

While German tourists visiting Dresden are no longer quite as shocked by the old buildings they see everywhere, they do still irritate tourists from abroad. Everything around the Frauenkirche smells of renovation and Disneyland so one is made aware of the reconstruction. However, questions start to – arise at the very latest – on the way to Pillnitz, via the villa quarter Blasewitz and the ‘Blaue Wunder’ [Blue Wonder] Bridge. How could all of this have survived the firestorm? After all, it was a second Hiroshima, wasn’t it?

The Nazi leadership used the air raids on Dresden on the 13 and 14 February 1945 as the basis of a campaign to discredit the allies in neutral countries abroad. In the days following the bombardment the news agencies filed detailed reports, press releases and radio reports which represented Dresden as a peaceful city of art and culture.1 The lies propagated by the Reich Ministry of Propaganda about the innocent, militarily unimportant art and culture city which had been unnecessarily bombed shortly before the end of hostilities while talking about a hundred thousand deaths, a rain of phosphorus and low-flying fighter planes targeting the civil population were not without effect in the allied and neutral nations. Although critical historians and anti-fascist groups active both in local and national discourses have been successful in deconstructing the Dresden-as-victim myth over the last few years international perception of the air raids on Dresden are nevertheless regarded as militarily senseless, particularly savage or even as an Allied war crime. The reception of classics of literature such as Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse 5 continue to contribute to this. In his book, a high school text in the USA, Vonnegut compares Dresden after the bombing with the surface of the moon and quotes David Irving, the British revisionist historian and Holocaust denier who, in The Destruction of Dresden, published an exaggerated numbers of casualties – 135,000.

Also involved in the internationally current idea that one has to place Dresden and Hiroshima (and 11 September too) in the same category is bestseller author Jonathan Safran Foers. In his book, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close,which was filmed in 20112 he links the story of his main character with the experiences of his grandparents who lived through the Dresden bombings. In Germany parallels like this drawn by outsiders are gratefully accepted. Thus the conservative Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung wrote: ‘Moreover, the New York drama is interlaced with two other apocalyptic firestorms, viz. the bombing of Dresden and the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima. Thus Foer relates two of the most contentious and symbolically charged catastrophes of the twentieth century to a terrorist crime which, we fear, will become no less symbolic for the beginning of the twenty-first century’.3 By translating our criticisms of memorialisation we intend to intervene in the continuing reproduction of the Dresden myth in international discourse. We would like to make our arguments against the memorialisation of the bombing accessible to academics, political activists and those interests outside German-speaking regions.

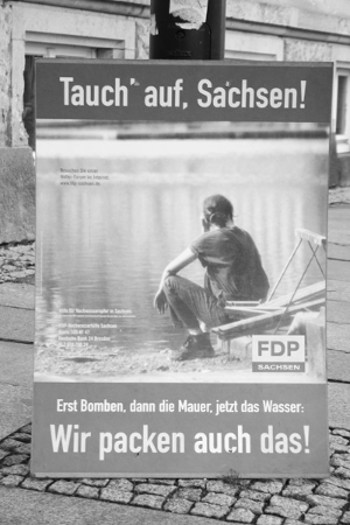

‘First the bombs, then the Wall, now the floods: we can handle that too!’

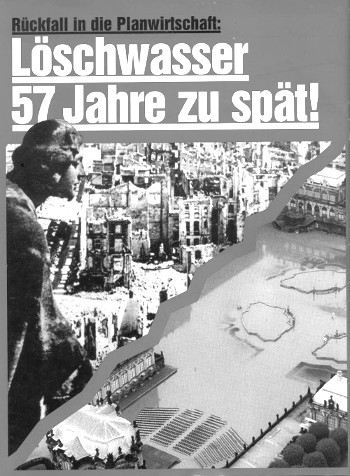

This morale-boosting slogan brightened the summer of 2002 – the ‘flood of the century’ had just turned ‘Florence on the Elbe’ into ‘Venice on the Elbe’ – on a short run of posters distributed by the Saxony FDP [Free Democratic Party] calling for donations for its flood fund. It could only be seen in Dresden city centre. Dresden, after many hard setbacks of fate, knows what suffering and privation mean. Anyone wanting to score points in Dresden would do well not to forget the bombings – they give you a direct line to the identity of its inhabitants. A fixed point of reference is their collective memory of the Allied air raids on Dresden between the 13 and 15 February 1945. And none of this is a joking matter, as one can see from the reaction to Thomas Gottschalk’s witty remark during the television programme, Wetten, dass …? when he commented on the rebuilding the Frauenkirche [Church of Our Lady but literally ‘Women’s Church’] by asking if it might not have been cheaper to build a women’s parking space. There was a similar reaction when the satyric magazine, Titanic, commented the 2002 floods on it back page with ‘Relapse into a planned economy: water for extinguishing fires 57 years behind schedule’. Natives of Dresden vented their ire and dented pride in their suffering with angry articles and commentaries in local newspapers and letters to the editor.

Emerge Saxony! First the bombs, then the wall, now the floods: We handle that too!

Posters distributed by the Saxony FDP (Free Democratic Party) in 2002, calling for

donations for its flood fund. Photo: »Dissonanz« Author Collective

Dresden is legend, a beautiful, innocent city of art and culture and the German victimisation narrative without peer, bombed unnecessarily shortly before the end of the war with hundreds of thousands dead. It is a legend of ‘Allied war crimes’ with a rain of phosphorus, low-flying fighters targeting the civilian population. And it is a symbol of peace and reconciliation. In the meantime, for those who, in their political position in relation to memorialisation, are beyond legends and prefer to ‘put the past behind us’, Dresden has become a symbol for accurate memory as opposed to historically revisionist version of the Nazis. For a long time Dresden’s history only began on the 13 February 1945 with the bombardment of the city. Before that there was a long blank reach as far back as the glorious times of the Baroque era which were viewed through rose-coloured glasses: Dresden the Baroque pearl of art and culture. And little has changed up to the present.

National Socialism, the persecution of Jews, deportations, book burnings, force labour and Aryanisation – none of this took place in Dresden. Instead, the city was the personification of German victimhood that must, at last, be commemorated. The internationally effective myth of the lost city penned by Nazi propagandists and tenaciously cultivated over the years endures. But the annually increasing attention paid to the growing size of the Nazi procession – first established in Dresden in 1998 – had taken advantage of the form and content of the commemoration. This forced a change in the official remembrance and memorial policies – at least superficially. The legends were questioned, facts researched and the Nazi history of Dresden described and named. The city’s need re-draw the demarcation lines was satisfied by official declarations of belief.

To many that looked as if criticism of the annual commemorative ceremonies was now obsolete. For many others it seemed that from now on the only struggle required was that against the Ewiggestrigen [die-hards, literally ‘the eternal yesterdayers’] who were here to take part in one of their last great parades. Whereas in the 1990s the protests were directed against the annual remembrance evening of the 13 February in front of the Frauenkirche with its historical revisionism and denial of historical facts, one’s own guilt and perpetrator status, the protests in the last few years have focussed on preventing neo-Nazi parade marches. This was first fully successful (at least as far as the larger of the two annual processions is concerned) in 2011 when mass blockades were set up. However, much was lost sight of in the process especially and increasingly issues linked to the politics of memorialisation: an analysis of the linkages between the Nazi marches and memorialisation in Dresden and, equally, well-found criticism of Dresden memorial culture and the way in which guilt and perpetrator status in National Socialism was dealt with throughout Germany. There were also only marginally perceptible advances in criticism related to new developments in memorial discourse. Criticism that does more than deconstruct legends or contextualise events in a more than an abstract way is almost completely absent or even regarded as superfluous – the historical context of the bombing is common knowledge, isn’t it? Nevertheless criticism can still be made of memorial culture in Dresden, embedded as it is in the German victim discourse and with the German resistance to dealing with the National Socialist past.

In putting this book together the editors were motivated by this lack of closure deriving from a failure to grapple with the issues and the continuing necessity for critical interventions. They have all been politically active in Dresden for many years and are concerned with the critical analysis of memorialisation, the Dresden legends and their linkages with the discourses relating to the politics of memorialisation. They were (and are) members of various groups and projects which, over the past few years, have attempted to intervene in the annual events centred on the 13 February and the Dresden memorialisation discourse in general. Over these years much has been written, researched, restructured and discussed about the 13 February complex. Making this available to interested readers as a compendium was additional incentive for the editors.

‘Relapse into a planned economy: water for extinguishing fires 57 years behind schedule’ Published overleaf in September 2002 issue of Titanic Satire Magazine. Photo: Titanic

The articles by various authors that are collected here provide an overview of the basics: the socio-political content of and the developments around how the 13 February is commemorated. And they deliver a fundamental critique of this as well as the current German politics of memorialisation in general. The articles open up a chronological perspective of the development of the 13 February, looking at its anti-imperialist spin in the GDR, the Germans-as-victims attitude, the call for peace and conciliation as part of the new German self-confidence after 1990, the ‘truthful’ remembrance without exaggerate numbers of fatal casualties, low-flying fighter planes or blatant rejections of guilt and, finally the arrival in the Berlin republic. The texts offer an analytical perspective dedicated to individual aspects, discursive topoi and, equally, to symbols and their effects on the Dresden memorialisation discourse. But the present publication does not only link the publishers/editors because of their aspiration to provide descriptions, analysis and criticism but also because of their practical approach to the documentation of the various ways that have been tried since the 1990s to counteract and disrupt what can be called the Dresden fact-resistant mourning collective. This is always concerned with itself and a memorial discourse that is tightly bound up with their own identity as victims. At least some of their certainties have been shaken.

These articles are prefixed by a theoretical basis for further engagement with the 13 February complex. In Werkzeug Erinnerungskultur. Die Funktionen des kollektiven Gedächtnisses [Instrumental Memory. Functions of Collective Remembering] Mathias Berek takes on Dresden memorial culture and providing readers with a theoretical introduction to collective memory and memorial culture. He explains how collective memory is generated with regard to present motives and situations, the function it can have in defining politics, identity and reality and why this means that there can be no such thing as the ‘misuse of memory’.

In the chapter FOKUSSIERT [FOCUSSED] a number of different authors take up individual aspects of memorialisation in Dresden. The essay, Im Kielwasser. Der Mythos Dresden und der Wandel der deutschen Nationalgeschichte [Dresden in the wake of Germany: The myths of Dresden and the modification of German national history] sets current Dresden memorialisation in relation to the modernisation of German national history. In it, Henning Fischer pursues the question as to the role that the transformed discourse takes in the newly adjusted relationship of the Berlin republic to German history.

In Manna vom Himmel4, an interview mit audioscript Dresden, Olga Horak described the bombing of Dresden in January 1945: ‘During the raid we watched as bombs fell like manna from heaven’. She was one of the Jewish prisoners on death marches that passed through Dresden’s inner city area in January and February 1945.

In her article, ‘Da seht ihr’s, jetzt wisst ihr’s’:Friedenspolitische Initiativen im Gedenken an die Bombardierungen Dresdens seit 1980 ["Look around you, now you know." Politics of peace initiatives within the context of the commemorations of the bombing raids of], Claudia Jerzak describes the dilemma that actors who criticise military solutions to social conflicts have in historically de-contextualising the air raids on the one hand and, on the other, encouraging the propagation of the highly symbolic universalisation of the mythic narrative of the innocent city of art and culture to provide fertile ground for revisionist arguments.

In One Nation on the Screen: ‘Dresden’, filmisches Erinnern und deutsch-deutsche Geschichtspolitik [Filmic Commemoration and German-German Memory Politics] Antonia Schmid analyses how German television productions are dedicated to the quest and yearning for German identity. While marking the ideology of community as found is found in National Socialism as negative, they simultaneously manage to create the notion of victimised communities which proffers another identity.

The contribution by Christine Künzel, Slaughterhouse Dresden: Literarisches Erinnern bei Kurt Vonnegut und Jonathan Safran Foer – zwischen Satire und Kitsch [The Literary Memories of Kurt Vonnegut and Jonathan Safran Foer – Between Satire and Kitsch] undertakes a critical academic and literary analysis of the two American novels in which the destruction of Dresden plays a central role – the 1969 bestseller Slaughterhouse-Five or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty Dance with Death and Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close from 2005.

Two articles are focussed on those sites of remembrance that are central to Dresden inhabitants’ memorialisation of the bombings. While Swen Steinberg is concerned with the official memorial site of the City of Dresden, Heidefriedhof, [lit. Heath Cemetery], Philipp Klein pursues the history and significance of the symbol for the 13 February 1945 and post-war reconstruction that has been staged for the citizens of Dresden as the embodiment of peace and conciliation – the Frauenkirche. In contrast, in his contribution, Nicht Gedenkort, sondern Lernort – Was der Dresdner Heidefriedhof erzählt und erzählen könnte [From Memorial Space to Learning Place Present and prospective (hi)story telling at the Dresden Heidefriedhof / Heath Cemetery ], Swen Steinberg approaches his subject from the angle of the problematic memorial architecture and thus opens up a field for ways of dealing with memorial site education where memorials represent the ideology of remembrance of their times.

This focus on two of the most prominent symbolic sites is expanded by Philipp Klein’s overview of memorial politics in Dresden which is caught up in the identity dissonances inherent in the conflicts between reconstruction and victimhood. The spectrum of public memorialisation, from the Neumarkt [New Market] of the Baroque fundamentalist via the Trauernde Mädchen im Tränenmeer [The Mourning Girl in a Sea of Tears] to the current undertaking of a site of remembrance at the Busmannkapelle (a side chapel of the Sofienkirche) with the long-demanded memorial bearing the names of all 19,000 known fatal bomb causalities shows the continuing historical revisionism of the Dresden victim myth.

A completely different genre of text bears the title, Dresden Christ Superstar. Eine Farce in fünf Akten [A Farce in Five Acts]. It follows the Pathway of Remembrance in Dresden through its stations from ‘destruction’ to ‘resurrection’. Here, the fluffy Pink Rabbit delivers a commentary on staged events whereby Dresden does not only catch up with Jesus but overtakes him. In the end Dresden beats Jesus two to one. In their contribution, Dresden ruft [Dresden Calls] The Dresden Antifa Recherche Team (ART) traces the development of the largest Nazi march in Europe. They consider its significance inside the Nazi scene and, equally, the deeper linkages of the Nazi ‘mourning march’ with Dresden’s memorial culture. In Gedenken per Gesetz [Legislated Commemoration] the group looks at the new laws regulating assemblies in Saxony. With the passing of the assembly law, first in January 2010, subsequently overturned in 2011 by the courts only to be passed again in 2012, the CDU/FDP (conservative and liberal coalition) succeeded in creating a legal régime in Saxony that not only puts National Socialism on the same footing as communism but also intervenes in the discourse of memorial politics and the political domain per se.

The chapter CHRONOLOGISCH [CHRONOLOGICAL] undertakes a historical classification and contextualisation of Dresden during the period of National Socialism and well as a chronological account of memorial practices in the city. In ‚Plötzlich’, ‚Unerwartet’, ‚Sinnlos’ [‘Suddenly’, ‘Unexpectedly’, ‘Senselessly’] René Haase presents Dresden’s history before and during the Nazi period and shows how, in the light of historical facts, the claim the Dresden was an exception to history was correct but incomplete. This is because the National Socialist Gauhauptstadt [provincial capital] Dresden had, at certain levels, a special and even pioneering role so that the fairy tale about the ‘innocent’ and ‘militarily unimportant’ city on the Elbe has always been completely untenable. For almost seventy years now, the bombing of Dresden on the 13/14 February 1945 has been a fixed reference point in the memory and commemorative events in the city. Throughout those decades Dresden was the culmination and expression of the prevailing politics of history – from the anti-fascist and anti-imperialist position of the state in the GDR, via the closure (forget about the past – a ‘clean sheet’ restart) mindset and the new German self-confidence of the 1990s to the present-day memorial politics of the Berlin republic. In Gestern Dresden, heute Korea, morgen die ganze Welt ["Yesterday Dresden, today Korea, tomorrow the whole world."] Sophie Abbe describes the beginnings and development of an ideological spin imparted to the 13 February commemorations in the Soviet-occupied zone and the GDR. She investigates the question as to what signs and political contexts an anti-imperialist rhetoric in the historico-political discourse about National Socialism and the Second World War was established and, naturally, exercised an influence over the form and content of memorialisation in Dresden.

In Aus alt mach neu [Make do and mend] Andrea Hübler describes two decades of the history of Dresden commemoration in unified Germany. In the process she focuses on the developments of meaning and content – from the closure mindset, the erasure of historical context and the stylisation of Dresden as a symbol of peace and conciliation to a modernised form of remembrance in which Dresden, in keeping with the times, acknowledges its past and carries its having-learned-from-it confession before it like a banner and now, every 13 February, claims everyone’s suffering for itself.

The final chapter, AKTIVISTISCH [ACTIVIST] looks back on twenty years of critical engagement with commemoration in Dresden. Various approaches to dealing with, and the interventions opposing, annual events in Dresden around the 13 February anniversary are presented in a chronology of protest.

In an interview Krischan, a representative of the Antinationalen Gruppe Hamburg [Hamburg Anti-national Group] reports on the various activities of his group who are critical of commemoration. He recounts the 1993 journey of the Hamburg Wohlfahrtsausschuss [Welfare Committee, ] through Eastern Germany under the catchphrase Etwas Besseres als die Nation [Somewhat better than the nation], the heated discussions during the preparation of a poster campaign for Dresden and from the return of the Antinationalen Gruppe Hamburg two years later for the 50th anniversary of the 13 February.

The article, Auch weil niemand um Verzeihung bat. Die Geschichte des Pardons ist in Auschwitz zu Ende gegangen [But who ever asked us for a pardon? Pardoning died in the death camps.] by Heike Ehrlich and Kathrin Krahl discusses the audio tour of the city, the audioscript zur Verfolgung und Vernichtung der Jüdinnen und Juden in Dresden 1933 - 1945 [audioscript on the Persecution and Annihilation of Dresden Jews 1933–1945], which was produced as a counter-narrative to the hegemonic commemorative discourse and which lends weight to the memories of Shoah survivors and provides space for the analyses of critical philosophy.

»Dissonanz« Author Collective

translated by Tim Sharp

Download PDF of

the text.

1 Thomas Fache, Allierter

Luftkrieg und Novemberpogrom in

lokaler Erinnerungskultur am Beispiel Dresdens, Masters thesis,

TU

Dresden 2007: www.qucosa.de/fileadmin/data/qucosa/documents/6440/Thomas_Fache_Magisterarbeit.pdf

2 Director was Stephen Daldry, who also made Bernhard Schlinks revisionistic book „Der Vorleser“ [The Reader] into a film

3 Hubert Spiegel, Oskar allein in New York, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/buecher/rezensionen/belletristik/oskar-allein-in-new-york-193747.html (accessed November 18, 2014)

4 The Hebrew Bible mentions manna (or bread from heaven) in Exodus 16:1-36. It was the legendary food which sustained the Israelites on their 40 year of wandering the desert.