“LOOK AROUND YOU, NOW YOU KNOW.”

Politics of peace initiatives within the context of the commemorations of the bombing raids of Dresden since 1980.

by Claudia Jerzak

Initiative 1982: The peace movement as outlet for criticism of the system

At the time the whole thing just started as something spontaneous. Following up on a conversation, Johanna sat down at her parents’ typewriter (…) What [she] had in mind was some kind of romantic sit-in for peace.(…) But then there was this quite enthusiastic response. 1

Roman Kalex2 was a co-initiator of the protest that took place beside the Frauenkirche [Church of Our Lady] on 13 February 1982. The occasion he depicts as a happening carried out by hippies high on flower-power set off a wave of repression at the time. What evolved out of it over the next few decades ultimately became one of the central rituals of the Federal Republic of Germany’s commemoration of the German victims of the Second World War.

This article does not aim at recounting how it came about that the somewhat recklessly and casually initiated protest very clearly became a serious threat to the SED’s [Socialist Unity Party] ideological monopoly on the subjects of rearmament and militarization. Initially, the pacifist protests were implicitly set off against the negative foil the National Socialist dictatorship, carried or at least condoned by the population (Lüdke, Bajohr). The really important question here is how this pacifist protest metamorphosed into a de-contextualized commemoration of victimhood.3 What also becomes clear is that, in the course of subsequent historical generalizing and de-contextualizing, the focus on the cause of peace offered different religious and political groups, in particular from the extreme Right, the opportunity to participate in the movement.

Initially, however, the Friedenskreis [peace circle] protest was above all an expression of anger and contradiction within the GDR society, which had no provision for discourse or participation. Through the historical de-contextualizing reference to Dresden as a symbol of peace, the initiators thus involuntarily fortified the narrative of victimization in Dresden. The lack of any historical or political discussion on National Socialism or the Second World War in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), allowed the group (later Wolfspelz) to remain uncommitted in this respect. It was not until the mobilization of the extreme Right became visible in the mid-1980s4 that these blank areas received some attention.

After a relatively quiet phase in the culture of remembrance in the 1960s and 1970s5, the commemoration of the bombing raids on Dresden was re-vitalized by the critical young pacifists’ initiative in 1982.6

In 1981 a loosely-knit group of young people emerged in Dresden. They were members of churches, and also part of the hippie movement and they met up in downtown Dresden or in cafés such as the Mokkastube. A few of these young people – Johanna Kalex (real name Anett Ebischbach), Torsten Schenk, Oliver Kloß, Nils Reifenstein and Mac Scholz – decided to ‘express their desire for peace’7.

Their initiative was part of the worldwide peace movement that had been gathering momentum since 1977. Around that time people became aware that the USA was working on a neutron bomb, and the NATO Doppelbeschluss [NATO Double-Track Decision] led to million-strong protest marches, starting in 1979 and continuing for years. The Double-Track Decision meant the deployment of the US medium-range Pershing II and cruise missiles to Europe as a reaction to the stationing of Soviet SS-20 missiles. People were afraid that the US would defend its interests by means of a nuclear war in Europe. In addition, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979.

Johanna Kalex had the idea of holding a protest after hearing a friend describe a Roman Catholic pilgrimage to Poland where people laid out candles in the form of a cross and held prayers for peace. A year earlier the free trade union Solidarność had been founded with some support from the Catholic Church, so a transfer of symbols from one system to another had been established.

In October 1981 Johanna Kalex handed out 12 leaflets that she had typed up herself. Within hours a lot of others reproduced the hand-outs and distributed them. Over the next couple of days Elke Schanu illegally printed several thousand using the newspaper printing press of the Sächsische Zeitung. The initiative was well received in the circles of “latterday hippies”, as Roman Kalex refers to them, both in Dresden and in the GDR in general, and thus the information on the planned peace event was widely circulated between October and February.

In their leaflet for what they referred to as a commemoration service the initiators laid out the order of ceremony:

- 09.50 pm we all meet at the Frauenkirche

- Everyone is to bring a flower and a candle

- The flowers will be laid down to form a cross that we will sit around in a wide

circle with our candles in front of us (don’t forget matches)

- 10 pm tolling of the bells

- We wait for about two minutes

- Then we sing “We shall overcome”

There is to be complete silence the entire time. No talking whatsoever.8

Johanna Kalex wanted “to get across the idea that if you want to have peace, you can’t start wars.”9 She regarded the re-armament measures in the East (and West) as contradicting and undermining the GDR’s image of itself as an anti-imperialist Friedensstaat [peaceful state],10 propagated in keeping with Dimitroff’s theory of fascism11 and very much in evidence in Dresden commemorations since the late 1940s. She questioned the GDR version of the Cold War, summed up as “We are being attacked. We are the good guys”12.

Commemorations of the bombing raids on Dresden - mass rally with Hermann Matern on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the bombings.

Photo: SLUB Dresden / Deutsche Fotothek / Erich Höhne & Erich Pohl.

There were a variety of reasons for focusing on this contradiction within a commemoration ceremony on precisely 13 February. First and foremost, there was to be a solemn reminder of the bombing and a comment on the typical elements of the collective narrative of the population, namely that they had no knowledge and bore no guilt for National Socialism. Roman Kalex paraphrases the group's motto with the words “Look around you, now you know”. This interpretation of the past necessarily led to criticism of nationalism when it became clear that those critical were “not available for that kind of war. We don’t have that kind of relation with a Vaterland (…) that we would be willing to do anything for it.”13

Oliver Kloß for his part describes the choice of peace as rallying point as a means rather than an end: The right of assembly was anchored in the constitution but was in fact non-existent. This contradiction was to be made visible by means of an organized demonstration, provoking the state into its usual repressive reaction, and thus into delegitimizing itself. In appealing for peace the initiators could count on the solidarity of the population. Roman Kalex sees this differently: “It wasn’t until those early days in February that we realized there was potential for protest in the movement.”

Dresden presented a very visible case study of the results of military conflicts through its countless ruins – above all through the Frauenkirche, declared a memorial site as early as 1966. Within East Germany and beyond, it had become a symbol,15 in particular of the destruction resulting from the externalized war of conquest initiated by Nazi aggressors. The peace activists integrated this interpretation with the local significance of the memorial and anti-war day. The Staatssicherheit [state security (secret police)] noted at the time that one of the initiators criticized “how many of Dresden’s citizens [had] already forgotten the date.”16

In order to avoid repression for dangerous pacifist agitation17, the initiators of the event accepted the Lutheran Church’s offer of moving the proceedings to the nearby Kreuzkirche [Church of the Cross].

In 1980, Christof Ziemer, the then superintendent of the church district of central Dresden had already applied for permission to hold a public commemorative service beside the ruins of the Frauenkirche.18 The occasion was provided by the ten-day peace vigils, which started in 1980 and called for a complete demilitarization of both German states. The accompanying symbol of “swords to ploughshares” was printed on fabric by Harald Bretschneider, state youth pastor, and passed on in the form of bookmarks and patches. It was to become the sign of the East German peace movement. Ziemer’s priority, even ahead of commemoration and questions of peace, was to stimulate a discussion on what led up to the bombing in Dresden, in particular the bombing raids by German forces in other countries.

Against the background of the current Cold War conflicts, engagement in the politics of peace became the fundamental position for activists of the time, and Dresden, particularly through members of its church circles, went on to exert significant influence in other parts of the GDR.19

The concerns of the Friedenskreis [peace circle]20 were taken up by the Lutheran church and were to be incorporated in a peace forum.21 On 13 February 1982 around 5000 people came to the Kreuzkirche.22 Church officials gave answers to questions handed in anonymously on such subjects as the Soziale Friedensdienst [social peace service], on the arrest of the pastor Rainer Eppelmann following his Berlin Appeal23, and on the “possibility of non-violent resistance” in the event of a military occupation of the GDR24

According to Stasi records, the peace forum ended around 9 45 pm. “Approximately 400-500 young people, most of them between 15- 18 years old, met in groups and twos and threes in the ruins of the Frauenkirche. They moved there in an orderly fashion; there was no form of organization apparent. Approximately 50 candles were lit by the young people.”25 Then until 11pm they laid down flowers, sang “We shall overcome” and “Where have all the flowers gone” and set up a cross made of a couple of rough boards with “35,000 dead – why” written on it. The Stasi is satisfied.26

Public demonstrations based on private initiatives were only

possible within limits in the

GDR. This regulation led to the specific symbolic and ritual form of

the peace circle’s events: the initiators’ invitations always called

for participants to bring flowers and candles, and to maintain complete

silence during the remembrance. Ziemer describes the candle as a sign

of hope, devotion and non-violence, adopted from the Taizé brothers who

were touring through the GDR at the time. Roman Kalex regarded the

candle simply as a symbol of a better world. The silence in which the

act of commemoration took place was to reduce the risk of repression

from the authorities, but was also intended as counterpoint to the long

propaganda speeches of the SED [Socialist Unity

Party], full of repetitions and slogans.”We shall overcome” was a

deliberate reference to the civil rights movement. 27

Commemoration on the occasion of the 38th anniversary of the Dresden bombings on the Neumarkt in February 1983.

Photo: SLUB Dresden / Deutsche Fotothek / Rainer Siegert.

Thus the symbolic structure of the silent commemoration was composed of several elements: the reference to the peace and civil rights movements; the use of Christian iconography, which was common even among non-religious groups, given that the GDR opposition often operated under the protection of the church; and Ziemer’s initiative. Traditional symbols and contemporary sign systems were combined into a secular-Protestant ritual (Karl-Siegbert Rehberg). Consequently the Frauenkirche became a space both for protest and for commemoration. There was little reflection after 1989/90 and in the 2000s on the political conditions of the time that gave rise to and legitimized the silent ceremony of commemoration as a ritual.

Peace movement and silent commemoration in the 80s: between confrontation with National Socialism and a resurgence of nationalism.

The initiators

of the Friedenskreis no longer took part in

its activities as early as 1983: instead in 1985 they gave concrete

form to their reflection on Germany’s guilt and responsibility in the

Second World War and National Socialism in an exhibition “…oder

Dresden” (“or Dresden”)28. The commemorative site of

the Frauenkirche was nonetheless used

from 1982 as a space for protest. It thus influenced the development of

the silent commemoration form in the 1980s, which in turn led to the

legend of the Friedenskreis being the origin of the

“peaceful revolution”.29

In the post-Wende [Fall of the Berlin

Wall] depiction of oppositional groups, Wolfspelz was often

presented as

following the same line as conservative church groups who based their

activities on their critical distance and rejection of socialist ideas.30

Wolfspelz was even linked to

those who simply wanted to leave the GDR, though less for political

reasons. “Starting in 1987, a lot of people with suitcases turned up,

hoping to speed up the process of getting out of the country (…)”. “We

had a different agenda: the question of what a society that was

socialist and allowed citizens to participate fully could look

like”,

said Roman Kalex.31 The Federal German president

Roman Herzog, in his 1995 speech in the Dresden commemoration service,

assumed that the group was in fundamental opposition, and suggested

that it potentially subscribed to West German criticism of East Germany

and was in fact aiming at re-unification.32

The development of the silent commemoration form was not just subject to tension from outside and from within. In the struggle over the competing historical and political readings of events, which was re-ignited from 1989 onwards, the significance attached to the Frauenkirche, as a site of cultural remembrance, increased. This became apparent as early as December 1989, when in his speech the German chancellor Helmut Kohl chose the following formulation in the ruins of the Frauenkirche: “And here in this very place [!], before all of you, I want to extend this pledge and to swear: in future only peace shall ever come forth from Germany – that is the common ground on which we have come together!”33 This was the moment, at the very latest, that the Frauenkirche and Dresden became an all-German symbol that could be drawn upon to legitimize the Wiedervereinigung [re-unification]. From the day he took office, Kohl set off down the path from de-concretizing National Socialism34 to this proclamation of the “Unity of the Nation” in Dresden. With his inauguration slogan “Renewal means re-engaging with German history”35, he had placed the question of an all-German identity at the centre of Federal German politics.

Admissions of

guilt and

responsibility, like Federal German President Weizsäcker’s in 1985, or

accompanying gestures of reconciliation, like President Herzog’s in

1995 were not able to prevent a resurgence of the victims’

narrativeabout the so-called

civilian population in bombed German cities. If anything, they fuelled

activity to defend this exclusive victim status36.

Kohl’s pledge was immediately taken up by the citizens’ initiative for

the rebuilding of the Frauenkirche on the 12 February 1990

in the “Call from Dresden”: “We call for a world-wide response to

rebuild Dresden’s Frauenkirche and make it an

international Christian peace centre in renewed Europe (…) we call in

particular on the nations that waged the Second World War. We are

painfully conscious that Germany unleashed this war.”37

In reunited Germany: from peace to reconciliation

Since 1989/90, the influence of pacifist concerns within the culture of remembrance has diminished.38 In a parallel process to the reconstruction of the Frauenkirche the message of peace was replaced by the concept of reconciliation.39

Members of the

peace

movement criticized the re-construction of the Frauenkirche

because they feared it

would mean the loss of the admonitory character of the church as a

ruin. Furthermore, they feared that it would not be able to carry the

symbolic weight attributed to it through the unique circumstances –

wide-spread participation in its reconstruction, an international and

inter-generational common effort, the material evidence of

reconciliation. Several groups thus organized “GeDenken”

[ReFlect] an event

held from 2001 to 2007 in the Altmarkt [Old Market Place],40

considered to be an authentic site of remembrance. GeDenken was

discontinued as a

result of a number of those involved criticizing its lack of a clear

message, and accusing the organizing team of not being aware of the

need for a much stricter approach to the whole question of

commemoration of the bombing raids, in order to bring about changes to

the practices of remembrance. Furthermore, GeDenken had begun

to attract

revisionist groups.41

Despite their lack of consensus on content, almost all those active in Dresden had pacifism in common. The DGB [German Trade Union Council] and the ÖIZ [Ecumenical Information Centre] objected that the 13 February had become a worldwide “Day of Mourning” without becoming a worldwide Day of Peace. Far-right groups used the occasion in connection with their European meetings in Dresden and groups such as the Junge Landsmannschaft Ostpreußen [East-Prussian Territorial Youth Association] used the peace movement slogans, “War between brothers [civil war]– never again”. “Let there be no more war!” The CDU [Christian Democratic Party] undertook a further extension of the pacifist cause, clearly in keeping with various current interests, when they included the prevention of dictatorships and tyranny in their catalogue of messages of peace – the pointlessness of war and violence, the need for moral courage, the chances and benefits of reconciliation. As a result of these processes, a number of individuals in Dresden began to distance themselves from the de-contextualization and generalization of the perpetrator and victim roles. Instead they argued that their efforts lay on analyzing political and economic causes and effects, and thus on revealing the specific nature of National Socialism.42

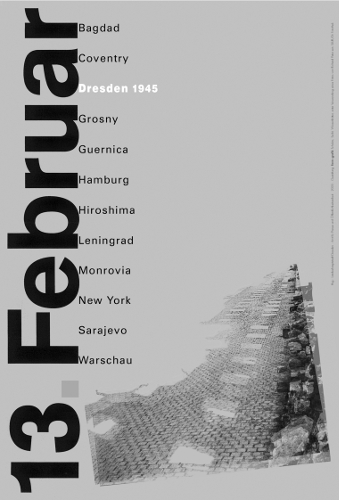

In spite of the later differentiation and alienation between groups, it can be said that after the Wende a broad spectrum of activists used 13 February to take up a position against the Gulf War, the wars in Yugoslavia and Iraq, and to protest against international intervention.43 This continuation of (de-) contextualizing through reference to other destroyed cities was adopted in the city’s posters and brochures,44 first printed to mark the 60th anniversary of the bombing raids in 2005, and used subsequently. This campaign, initiated by the city authorities, picked up the theme of the Stelenkreis [circle of columns] in the Heidefriedhof [cemetery]45 and extended its reference to other sites and times.

Official poster of the city of Dresden in 2005,

publisher Landeshauptstadt Dresden.

This construction of symbols within the culture of commemoration makes it quite plain that the hallmark of this pacifist engagement is generalization and subsequent historical de-contextualization. Through their reference to other cities destroyed in the Second World War and other wars, to other sites of destruction and to current military conflicts, the advocates of pacifism have become generalizers. Thus the extension both in space and in time has led to a collectivizing of all these sites into a pan-European or international community of victims.

Furthermore, the reconstruction of the Frauenkirche started a shift from the terminology of peace to that of reconciliation. This was a further step down the road towards de-contextualization, and had two consequences: ultimately it put an end to reflection on National Socialism - in the case of the Frauenkirche to any scrutiny of that church’s own role as a cathedral of the German Christians of that period - and secondly it allowed a switch of the perpetrator and victim roles,46 thus making calls for apologies from the USA and Great Britain possible.47 The question of reconciliation is almost entirely directed towards these countries, while individual victims of National Socialism are rarely addressed. It should be added here that starting with the Cross of Nails community in Coventry in 1965, a largely religious peace and reconciliation movement had become established. In connection with reconciliation initiatives with Coventry and Warschau, for example, the English city’s Bishop Gibbs said in 1985 in Dresden’s Annenkirche [Church of St Anne] that he felt shame towards Dresden and hope for peace.48

One can’t help but be somewhat puzzled and astonished: surely the primary victims of National Socialism should be the ones to offer reconciliation, and not the people of Dresden? Or as the historian Nora Goldbogen, head of the Jewish community in Dresden said, “Something different is important to us: remembering. (…) [Reconciliation] is not about you reconciling yourself with the others, but the others becoming reconciled with you. Or rather somehow managing to achieve this, by thinking about what you did wrong yourself, whether big mistakes or small ones.49

Citation Claudia Jerzak: “Look around you, now you know.” Politics of peace initiatives within the context of the commemorations of the bombing raids of Dresden since 1980., in: Abolish Commemoration – A Critique of the Discourse relating to the Bombing of Dresden in 1945, online at http://www.abolishcommemoration.org/jerzak.html [accessed dd.mm.yyyy].

translated by Teresa Woods

up

Download PDF

of

the text.

1 Roman Kalex in an interview for the documentary film „Come together. Dresden und 13. Februar” (in the following: Interview CT).

2 I am grateful to Roman Kalex for his willingness to answer all my questions about the situation in the 1980s and for his thoughtful contributions on the initiatives of the Friedenskreis, Wolfspelz and the Anti-Nazi-Liga.

3 In connection with the return of Germany’s memorializing of victimhood and de-contextualizing in the heated debate during the ‘Super Commemoration Years’ 1993-95 over the bombing of cities cf. Malte Thießen Eingebrannt ins Gedächtnis. Hamburgs Gedanken an Luftkrieg und Kriegsende 1943 bis 2005, Hamburg: Dolling und Galitz Verlag, 2007 p 316ff; in the 2000s s. Martin Sabrow: „Den Zweiten Weltkrieg erinnern“, APuZ, 36-37, 2009, pp 14-21, hier p 19 ff and also the central role of the Dresden commemoration ceremonies cf Harald Schmid: „Deutungsmacht und kalendarisches Gedächtnis – die politischen Gedenktage“ in Peter Reichel/Harald Schmidt/Peter Steinbach (ed.): Der Nationalsozialismus – Die Zweite Geschichte. Überwindung – Deutung – Erinnerung, München: CH.Beck, 2009, pp 175-216, here p 212ff.

4 Roman Kalex in interview CT.

5 Cf Michael Ulrich: Dresden – Nach der Synagoge brannte die Stadt, Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2002 and Matthias Neutzner: „Vom Anklagen zum Erinnern. Die Erzählung vom 13 Februar“ in Oliver Reinhard/Matthias Neutzner/Wolfgang Hesse (ed.): Das rote Leuchten. Dresden und der Bombenkrieg, Dresden: Edition Sächsische Zeitung, 2005, pp 128-168, hier p 157. Christof Ziemer, the then superintendent, spoke of a “formalized”, “ritualized” culture of remembrance (interview CT).

6 See also Claudia Jerzak: „Der 13. Februar in Dresden: Gedenkrituale, Wandel der Erinnerungskultur und ihre Demokratisierungspotenziale“, in Weiterdenken – Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung Sachsen/Kulturbüro Sachsen (ed.): “Sachsens Demokratie”? Demokratische Kultur und Erinnerung, Medienlandschaft und Überwachungspolitik in Sachsen, Dresden, 2012 pp 35-46.

7 Flyer, error in original, copy in author’s archive.

8 Flyer, error in original, copy in author’s archive.

9 Johanna Kalex in interview CT.

10 Dimitroff’s definition of Fascism: “When Fascism rules, comrades, it is the open, terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, chauvinistic imperialistic elements of finance capital. (…) It is a system of political banditry, a system of provocation and torture of the working classes and of the revolutionary elements of the peasantry, the lower middle class, and the intelligentsia.” (Georgi Dimitroff: Ausgewählte Schriften 1933-1945, Cologne:Verlag Rote Fahne, 1976, p.97).

11 As a result of the founding of two separate German states the subject of peace became the central issue in the commemoration in 1950, and “Anglo-American bombers” and “American war-mongers” became the new enemy, along with the FRG as the “successor state to the Third Reich”.

12 Johanna Kalex in interview CT.

13 Roman Kalex in Interview CT. He summed up their attitude: “And we didn’t find the idea at all sexy that we should put an end to our fairly young lives because a couple of people felt their Vaterländer had to be defended against one another.”

15 Cf.Tony Joel, „Reconstruction over Ruins. Rebuilding Dresden’s Frauenkirche”, in Martin Gegner/Bart Ziino (ed.): The Heritage of War, London: Routledge, 2011, pp 197-218, here p 204. Furthermore cf. the contribution Frauenkirche-Mania von Philipp Klein in this volume.

16 BStU, Archive of the Außenstelle Dresden, Reg.-Nr XII 33/82, „Ruine“, Vol.25.

17 Cf ibid, Vols.45,47.

18 Cf Olaf Meyer: „Erinnern und Trauern als öffentliche Ausdrucksformen der christlichen Gemeinde. Das Beispiel Dresdens“, in: Werner Dannowski/Wolfgang Grünberg/Michael Göpfert/Günter Krusche (ed.): Erinnern und Gedenken (Kirche in der Stadt, Bd.1) Hamburg: Steinmann und Steinmann, 1991, pp 62-69; Ulrich, Dresden, 2002, op cit.; cf also Christof Ziemer: „So on my first venture into the city hall I asked the deputy mayor, (…) whether I could go to the Frauenkirche on 13 February and hold a service there. (…) And two days later they told me that regretfully it was not possible, and that church activity naturally had to be confined to within church premises and not take place in public areas.” To get around this Ziemer held an introductory service, after which 500 people remained to pray for peace. (interview CT).

19 Cf also Josef Schmid: „Sozialethisch engagierte Gruppen in Dresden“, in: Detlef Pollack/Dieter Rink (ed.) Zwischen Verweigerung und Opposition. Politischer Protest in der DDR 1970-1989, Frankfurt am Main 1997, pp 171-187.

20 As a response to their experiences on13 February, some young people founded the Friedenskreis with the aim of holding a well-publicized demonstration on 1 May. During the exhibition “…oder Dresden” the state bishop Hempel commented on the group’s standpoint, describing them as wolves in sheep’ clothing or sheepskins. The group saw themselves in exactly the opposite role and called the group Wolfspelz [Wolfskin].

21 In the years that followed and up to this day the prayers

for peace are still the main emphasis of the commemoration ceremonies

of the Kreuzkirche on 13 February. Cf. Erhart Neubert, Geschichte

der Opposition in der DDR 1949-1989, Berlin: Christoph Links

Verlag, 1997, p 398; Claudia Jerzak, Gedenken an den 13. Februar

1945. Perspektiven Dresdner AkteurInnen auf die Entwicklung von

Erinnerungskultur und kollektivem Gedächtnis seit 1990,

Magisterarbeit an der Technischen Universität Dresden/Institut für

Soziologie, 2009. Download from www.qucosa.de/fileadmin/data/qucosa/documents/9901/Magisterarbeit%20_%20Claudia%20Jerzak%20_%20Dresden%2013%20%20Februar.pdf

(accessed December 11 2012)

22 “From around noon on 13 February 1982 young people in numerous groups and twos-and-threes moved in the city centre to the start of the service in the Kreuzkirche without signs of negative behavior”. At 5 pm they entered the church “in an orderly fashion” (BstU, “Ruine”, Vol.47).

23 The initiative was registered in the FRG (Die Welt, 10.02.1982, s 1) and to some extent placed in the context of the peace movement (cf. e.g. Berliner Morgenpost, 10.02.1982, p 1) West German television teams, including the two Federal German public-service channels, were present and the Stasi noted that there were radio reports.

24 BstU, „Ruine“ vol 48.

25 Ibid vol.49.

26 MfS-Oberst Böhm [officer in the Ministry for State Security] ends his report: “In sum it can be said that the political operative measures taken achieved the intended goal” (ibid Vol 50) – although the counter demonstration - torchlight procession and Kampfmeeting of the FDJ- Freie Deutsche Jugend (East Germany’s official youth movement) - planned for 1982 (ibid, Vol 23) did not in fact take place until 1983 onwards.

27 Interview Christof Ziemer and Roman Kalex CT.

28 Lutheran Superintendent of Dresden-Mitte (ed.) “…oder Dresden”. Fotos, Dokumente und Texte einer Ausstellung 40 Jahre nach der Zerstörung der Stadt, Dresden, 1987.

29 Cf Neuber, Geschichte der Opposition, 1997, op cit., p 398. The group connected with Harald Bretschneider were more focused on the Kreuzkirche and Friedensforum and saw themselves in the tradition of peaceful revolution. They set up their own memorial in front of the Kreuzkirche with the Steine des Anstoßes [stones of provocation]; cf. www.evlks.de/aktuelles/nachrichten/17110.html

30 Cf contrast to Schmid, „Gruppen in Dresden“, 1997, op cit. Also Neubert, Geschichte der Opposition, 1997, op cit.

31 Roman Kalex Interview CT.

32 “The citizens of Dresden in this procession [between the two churches as part of the ecumenical service- author’s note, CJ.] consciously resisted the attempts of the SED regime to turn the commemoration of 13 February 1945 into an anti-British, anti-American, and ultimately an anti-Western statement. Instead they protested and took the first steps along the right path (…).They showed that they were capable, entirely on their own, of overcoming the shadows of the past, and thus of opening the gate to a better future.” www.bundespraesident.de/SharedDocs/Reden/DE/Roman-Herzog/Reden/1995/02/19950213_Rede.html (accessed April 04 2009).

33 Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung (Hrsg.): Bundeskanzler Helmut Kohl. Reden und Erklärungen zur Deutschlandpolitik. Bonn, 1990, S. 141; Teltschik, Deputy head of the Chancellor's Office 1983-1990, on the relevance of this speech cf. Horst Teltschik, 329 Tage.Innenansichten der Einigung, Berlin: Siedler, 1991. ”We are all aware that the speech tomorrow will be a balancing act. It has to do justice to the hopes and feelings of those gathered in the church square, and at the same time the world will be listening and weighing every word.“(p 86), and “we are fully aware that it is a great occasion, a historic day, an experience that will be forever unique (…)“ (p.87); ”(…) The Chancellor thought about having the afternoon ceremony brought to a close with the hymn “Nun danket Gott”, so as to have a fitting vehicle for the emotions people were likely to feel, and also to prevent anyone singing the first verse of the German national anthem [Deutschland, Deutschland über alles – trans. note] (p.88): Against the backdrop of the ruins of theFrauenkirche: “The crowd chanted ‘Deutschland, Deutschland’, ‘Helmut, Helmut’ and ‘Wir sind das Volk’ [We are the people]. The Chancellor had a lump in his throat as he closed his speech with the words ‘Gott segne unser deutsches Vaterland’ [May God bless our German Fatherland]”. (p 91) Teltschik quoted Foreign Minister Genscher as having said in the cabinet meeting chaired by Helmut Kohl next day: ”The entire world witnessed that Germans have learned their lessons from history.”

34 Cf Sabine Müller, Die Entkronkretisierung der NS-Herrschaft in der Ära Kohl, Hannover: Offizin, 1998

35 Helmut Kohl, „Regierungserklärung des Bundeskanzlers vor dem Deutschen Bundestag“, Bulletin der Bundesregierung Nr 93, 14.10.1982, p.866.

36 Cf Dietmar Süß, Tod aus der Luft. Kriegsgesellschaft und Luftkrieg in Deutschland und England, München: Siedler, 2011, p 551, 553.

37 www.frauenkirche-dresden.de/en/building/reconstruction/appeal-from-dresden/ (accessed February 22 2008)

38 Michael Müller, former pastor of the Kreuzkirche thinks that the Lutheran church was much more pacifist in character in the 1980s as a result of the Cold War than it is currently, since it is now possible to become a conscientious objector, and the military is subject to democratic institutions. Furthermore, Müller points out that in the GDR church members who held senior positions in the army or the police were put under pressure to give up their membership. The result was a clearer line of confrontation between the church and the military. Cf. Claudia Jerzak, Gedenken an den 13 Februar 1945. Perspektiven Dresdner AkteurInnen auf die Entwicklung von Erinnerungskultur und kollektivem Gedächtnis seit 1990. Masters thesis at the Technische Universität Dresden/Institut für Soziologie, 2009 Download under: www.qucosa.de/fileadmin/data/qucosa/documents/9901/Magisterarbeit%20_%20Claudia%20Jerzak%20_%20Dresden%2013%20%20Februar.pdf (accessed December 11 2012).

39 Anja Pannewitz discovered in her media analysis that the Frauenkirche is described above all as a symbol of reconciliation (in just under 50% of the reports), as a sign of peace (33%) and of international and European understanding (28%), and as a warning against war, destruction, and collapse (27%). Cf. Anja Pannewitz, Die Symbolik der Frauenkirche im öffentlichen Gedächtnis. Eine Analyse von Pressetexten zum Zeitpunkt der Weihe 2005, 2007, www.weiterdenken.de/de/2014/02/21/die-symbolik-der-dresdner-frauenkirche-im-oeffentlichen-gedaechtnis-publikationen (accessed January 04 2015).

40 In choosing the Altmarkt, the organizers wanted to distance themselves from the Frauenkirche and to provide a contrasting event with different content, and with a reference to the burning of the corpses of the bombing victims.

41 Cf.Jerzak, Gedenken, 2009, op cit.

42 Ibid.

43 In 1991 the Gulf War was the focal point of the commemoration events, and there were slogans such as “Remember Dresden. Immediate ceasefire. Stop the War in the Middle East – negotiate.” It was also the focus of the prayers for peace, spoken within the ecumenical service in which Richard von Weizsäcker took part. (cf. Ulrich, Dresden, 2002, op cit. p. 78). In 1993 the war in Yugoslavia was the new focus (cf. Gunnar Schubert: Die kollektive Unschuld. Wie der Dresden-Schwindel zum nationalen Opfermythos wurde, Hamburg: KVV konkret, 2006, p 112). On 13 February 2003 survivors of the German bombing raid on Guernica together with survivors of the Dresden bombing read out an appeal against the Iraq War in the Frauenkirche; frieden-erinnern.org/grussbotschaft-aus-gernika-dresden/ (accessed January 04 2015).

44 The posters show the cities of Bagdad, Coventry, Dresden, Grosny, Guernica, Hamburg, Hiroshima, Leningrad, Monrovia, New York, Sarajevo, Warsaw; www.dresden.de/de/02/110/03/c_025.php (accessed January 12 2008).

45 See the contribution Nicht Gedenkort, sondern Lernort by Swen Steinberg in this collection.

46 This is very evident in the Flammenvase [vase of flames] in Gostyn; http://www.frauenkirche-dresden.de/flammenvase.html (accessed10.10 2012).

47 On the Queen’s refusal to say Sorry for Dresden see www.berliner-zeitung.de/archiv/die-queen-kommt-zu-besuch--eigentlich-sollte-das-ein-zeichen-der-versoehnung-werden-wenn-da-nicht-dieser-seltsame-streit-aufgeflammt-waere-die-deutsche-koenigin,10810590,10227322.html (accessed October 10 2012).

48 Cf.Meyer, „Erinnerung und Trauern“, 1991,a.a.o., p 69.

49 Nora Goldbogen Interview CT.